Parkland Florida High School Shooting

On Valentine’s Day 2018, as the co-founder of Parents Against Pharmaceutical Abuse (PAPA) was taking to the airwaves for a pre-scheduled appearance on the Dr. Peter Breggin Hour — to discuss the documentary Speed Demons: Dying For Attention linking the Florida State University (FSU) school shootings in 2014 to the stimulant drug Vyvanse — news was breaking of another school shooting in Florida at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

Within days, records would surface linking the Parkland shooter to the same class of drugs as the FSU shooter.

Seventeen students and adults were killed. Nineteen year-old Nikolas Cruz reportedly confessed to the attack to Broward County Sheriff’s Office.

A Florida Department of Children and Families investigative summary indicates Cruz, like FSU shooter Myron May, was taking medication for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

According to the DCF report, Cruz was “suffering form [sic] Depression, ADHD and which impair his ability to cope with the demands of everyday life without the use of medication.”

Cruz’s mother indicated Cruz “is on medication for the ADHD.”

Crisis Clinician Jared Broomfield with Henderson Behavioral Health reportedly stated “the information he obtain [sic] regarding [Cruz’s] medication is all up to date and correct.”

Counselor Sharon Urick reportedly stated “there was no concern that [Cruz] was taking his medication.”

Pharmaceutical companies coined the expression “off their meds” to offer an alternative theory of causation for school shootings other than their drugs, but as was apparently so here, it is often the case that the perpetrators of such violence were indeed taking their medications.

Many people don’t realize that the most commonly prescribed drugs for ADHD are methylphenidate and amphetamines. If you noticed that methylphenidate and amphetamine combined spells methamphetamine, then you get the picture. Stimulants prescribed for ADHD are in the Schedule II class of controlled substances, the same class of drugs as methamphetamine and cocaine.

In 1973, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Commissioner banned the amphetamine drug Obetrol, which as the name suggests was prescribed to control obesity. The FDA Commissioner ruled “Obetrol Tablets should be withdrawn on the basis of lack of substantial evidence of effectiveness and lack of proof of safety.”

Despite the drug having been banned and removed from the FDA’s Orange Book of approved drug products in 1973, the manufacturer continued to market the amphetamine drug in the United States. In 1982, the FDA inspected the manufacturer, collecting samples of the drug and noting that the company was marketing the drug without an approved New Drug Application (NDA).

If ordinary citizens sold an amphetamine drug in the United States without FDA approval, they would go to jail. Far from punishing the perpetrators, the FDA allowed the company to operate with impunity, continuing to market the drug without approval for another twelve years.

In 1994, the manufacturer of Obetrol took out a full-page ad in the Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology (JCAP), marketing the amphetamine drug under the trade name Adderall for ADHD.

A rare closed-door meeting was held at the FDA with company executives in 1995. During the meeting, the company’s attorney admitted that a reformulated Obetrol had in fact been marketed in the U.S. since 1973, despite the ban. As it turned out, the drug was still listed the whole time in the Physician’s Desk Reference (PDR), because doctors and pharmacists could easily get their hands on the drug.

The FDA allowed the company to submit a NDA for Adderall. In 1996, the FDA approved Adderall for the treatment of ADHD and narcolepsy, but not for obesity. Just like that, an amphetamine drug that had been banned but still marketed for over two decades was rehabilitated as a drug to help kids focus better at school, instead of a weight loss drug for adults. Adderall became the company’s biggest blockbuster until Vyvanse.

Florida public schools are notorious for pushing ADHD medications on parents and children, even though there is no reliable scientific evidence to support false claims that stimulant drugs improve long-term academic performance.

In 2014, Shire Pharmaceuticals, the manufacturer of Adderall and Vyvanse, settled a false claims case out of court for $56.5M. The lawsuit was filed by Dr. Gerardo Torres, a medical doctor and scientific leader of Shire’s ADHD business, who turned whistleblower. The federal government agreed with Torres, joining his lawsuit, along with 29 U.S. states, the District of Columbia and the City of New York. One of the primary allegations in the complaint was that Shire was making false claims that Adderall XR improves academic performance.

With $2B in annual sales of Vyvanse and Adderall, Shire essentially paid a parking ticket to not have to answer the allegations in court.

In 2015, the FDA came full-circle. With Vyvanse exclusivity expiring for ADHD, the agency approved the amphetamine drug for Binge Eating Disorder (BED), a controversial new disorder added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM 5) in 2013.

After a forty-year ban on amphetamine diet pills in the U.S., Shire and the FDA re-branded the ADHD drug Vyvanse as a weight loss pill. Shire provided the seed money for the Binge Eating Disorder Association (BEDA), and a new so-called patient or advocacy group was born.

Adderall, the ADHD drug formerly known as a weight loss drug called Obetrol, was then re-branded and FDA-approved in 2017 as a “new” 16-hour speed pill called Mydayis.

The Vyvanse and Mydayis labels warn: “Anxiety, psychosis, hostility, aggression, suicidal or homicidal ideation have also been seen.”

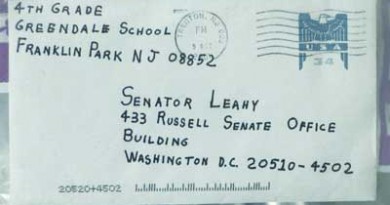

In 2015, the co-founder of PAPA successfully sued the FDA, under the Freedom of Information Act, obtaining over three thousand pages of adverse event reports (AER) linking psychotropic drugs to homicides. In court pleadings, the FDA admitted that documents responsive to the requests pertained to school shootings and other murders that received extensive press coverage.

The homicidal drug reports have been made available and searchable on this web site.

In 2016, the U.S. Department of Justice (DoJ) sent us a threatening letter, demanding we delete some of the documents the FDA had turned over to us disclosing credible medical assessments pointing to a causal role of the drugs in homicides. As politely as possible, we told them NFW. About the same time, the FDA admitted in court pleadings that the agency had not evaluated the reports, some of which were submitted to them over a decade ago.

Fast forward to 2018, and the FBI – part of the DoJ – has admitted that it failed to follow protocols with respect to following up on a tip that Cruz posed a school threat.

Florida Governor Rick Scott, who called on FBI Director Christopher Wray to step down due to the bureau’s lapse, bears ultimately responsibility for the agency which deemed Cruz as at low risk for harming himself or others. Scott has also received campaign contributions from stimulant drug manufacturers Novartis, Pfizer and Teva.

Florida is well-acquainted with the psychotic side effects of Vyvanse, the most commonly prescribed drug for ADHD, and so is DCF.

In 2009, 7 year-old foster child Gabriel Myers committed suicide on the drug, hanging himself in the bathroom of his Margate foster home, just fifteen minutes away from the carnage at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. The FDA sent a warning letter to his treating physician, Dr. Sohail Punjawni, citing violations of clinical trial protocols. In other words, DCF had allowed a foster child under the agency’s care to be used as a guinea pig for Shire. Needless to say, suicide is not a positive endpoint measurement for a clinical trial.

In 2017, 14 year-old foster child Naika Venant, whose dose of Vyvanse had recently been increased, streamed her suicide live on Facebook. Dr. Scott Segal was the prescribing physician who upped Naika’s dose of Vyvanse. His company, Segal Institute for Clinical Research, received over three hundred seventy thousand dollars from Shire between 2013 and 2015.

The FSU shootings in 2014 were also linked to Vyvanse. Toxicology revealed Myron May had .24 milligrams per liter of amphetamine in his system.

Victims: Alyssa Alhadeff, Scott Beigel, Martin Duque Anguiano, Nicholas Dworet, Aaron Feis, Jaime Guttenberg, Chris Hixon, Luke Hoyer, Cara Loughran, Gina Montalto, Joaquin Oliver, Alaina Petty, Meadow Pollack, Helena Ramsay, Alex Schachter, Carmen Schentrup, Peter Wang